The Many Lives of Che (pt. II)

In a previous post I raised the questions what does the image of Che Guevara mean and has the commodification of this icon depoliticized him? Ten months later I have some data, and now Omar and I are working out our ideas in a paper about collective memory.

The data come from a national survey of adults in Spain in 1991 and 1993. Among the battery of questions, is one that asks respondents to name two famous Latin American figures. The most common responses include revolutionary Simon Bolivar, author Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and far and away the most frequently mentioned figure, Che's old boss, Fidel Castro. Che also easily broke the top ten. The question that interests us, and one that we think can provide insights into the two questions driving this research, is who remembers Che?

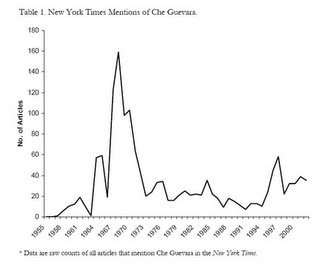

Karl Mannheim long ago hypothesized that generations of people are defined by their shared experience - and memory - of major political and social events (and, by extension, people) that occurred as they came of age (ages 18-25 in his mind). When applied to the Che question, we should expect that those most likely to recall Che came of age in the Sixties when he held national posts in the Cuban government and was killed in Bolivia. That period also marks his most visible years in the international press. The figure below shows the number of mentions of his name in the New York Times since 1955. The peak (1968) coincides with the year following his widely publicized death.

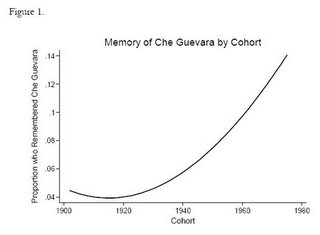

In our data, however, the pattern looks much different. The figure below shows respondents' years of birth and the likelihood that they mention Che Guevara. We do find a strong generational effect - i.e., age does matter - but not in the way Mannheim expected. Turns out that the baby boomers of the Sixties are significantly less likely to recall Che than their children. So this is the puzzle for our research: why are younger generations more likely to remember Che than their parents and grandparents?

In our data, however, the pattern looks much different. The figure below shows respondents' years of birth and the likelihood that they mention Che Guevara. We do find a strong generational effect - i.e., age does matter - but not in the way Mannheim expected. Turns out that the baby boomers of the Sixties are significantly less likely to recall Che than their children. So this is the puzzle for our research: why are younger generations more likely to remember Che than their parents and grandparents?

It might be that the commodification of Che has indeed depoliticized him. The young remember him because his image has reached a much wider audience who know little about his politics but avidly buy his t-shirts, posters, and key chains. Or, maybe the t-shirt industry isn't so powerful as to erase Che's politics from memory and social movements have successfully sustained him as a political symbol. If the latter is true, we ought to find evidence that those who remember Che are somehow more political or otherwise affected by social movements than those who don't. If not, perhaps he has become an empty t-shirt with all the political potency of Fruit of the Loom.

So...what's your prediction?

It might be that the commodification of Che has indeed depoliticized him. The young remember him because his image has reached a much wider audience who know little about his politics but avidly buy his t-shirts, posters, and key chains. Or, maybe the t-shirt industry isn't so powerful as to erase Che's politics from memory and social movements have successfully sustained him as a political symbol. If the latter is true, we ought to find evidence that those who remember Che are somehow more political or otherwise affected by social movements than those who don't. If not, perhaps he has become an empty t-shirt with all the political potency of Fruit of the Loom.

So...what's your prediction?